Between 1884 and 1947, from the year that Moses Fleetwood Walker played for the American Association’s Toledo Mud Hens until the Brooklyn Dodgers inserted Jackie Robinson into the lineup, the most prominent minority was American Indians. One of the most insightful chapters in Larry Ritter's classic, “The Glory of Their Times,” is based on his interviews with John Tortes “Chief” Meyers, the slugging catcher who played for John McGraw's New York Giants and, in his career’s twilight, for the Dodgers and Boston Braves, from 1909 to 1917. Although Meyers, a California Cahuilla Indian, had matriculated at Dartmouth and was better educated than most ballplayers, his peers often treated him poorly. Meyers answered with his bat, compiling a .291 lifetime batting average. His 1912 mark of .358 was second in the league only to the Chicago Cubs’ triple-crown winner Henry Zimmerman's .372.

From 1890 to the 1950s, the nickname "Chief" was attached to virtually every Indian wearing a baseball uniform, a subtle form of racism in a less enlightened era---the aforementioned "Chief” Meyers, Albert "Chief" Bender, a Minnesota Chippewa whose pitching led the Philadelphia A’s to 1910, 1911 and 1913 World Series titles, Bob “Chief” Johnson, one-quarter Cherokee, a five-time .300 hitter who knocked in 100 or more runs eight times for the Philadelphia Athletics, Allie “Super Chief" Reynolds, a one-quarter Creek and a member of the New York Yankees dominant 1950s teams. Some big-league Indian players avoided the “Chief” sobriquet, including the most well-known of them all, Jim Thorpe. The first Indian to reach the major leagues was Louis Sockalexis, an outstanding outfielder with the National League’s Cleveland Spiders from 1897 to 1899. Sockalexis was a Penobscot from Maine, who, like Meyers, attended college---Holy Cross--- before becoming a professional player.

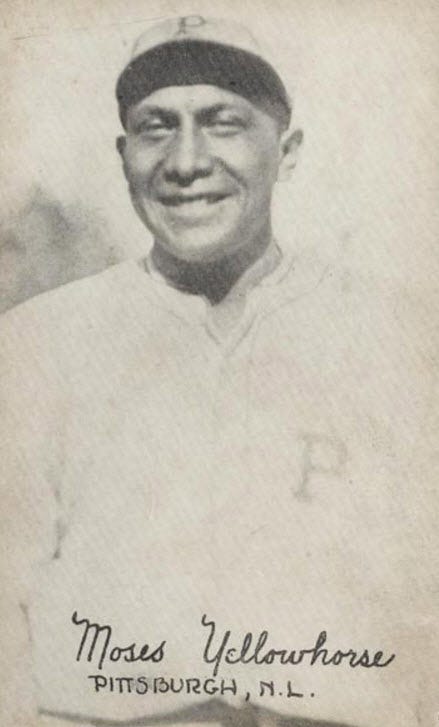

Moses J. “Chief” Yellowhorse was a Skidi Pawnee and the first full-blooded American Indian to play professional baseball. Born on January 28,1898 on an Oklahoma reservation where the federal government had forced his father’s Pawnee family and the rest of the Skidi tribe---or Wolf Band camps---to walk from their Nebraska camps to poor land south of the Arkansas river, Yellowhorse knew poverty early in life. Thousands died along the way; disease and starvation killed others in the following years. He and his father Thomas Yellowhorse worked on Pawnee Bill’s Wild West shows where young Yellowhorse got a reputation as a comedian with a fondness for alcohol. The government’s Indian agency directed that Yellowhorse attend the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, and there he developed his baseball skills. In 1917, Yellowhorse went 17-0 and moved up to the minor league Arkansas Travelers, where his reputation for unhittable pitches and alcohol-related exploits on and off the field spread across Oklahoma and into Arkansas. Batters who faced both Yellowhorse and Walter Johnson said the Pawnee’s fastball was speedier.

In 1921, Yellowhorse joined the Pittsburgh Pirates with high but unfulfilled expectations. Rooming with the alcoholic future Hall of Famer Walter James “Rabbit” Maranville accelerated Yellowhorse’s demise. In his two injury-plagued, and demon rum-filled seasons with the Bucs, Yellowhorse went 8-4 but gave up 137 hits in 126 innings. A fan favorite--- the cranks frequently yelled out from the bleachers, “Put in Yellowhorse!” --- the Pawnee’s ineffectiveness marked the beginning of his baseball career’s end. Yellowhorse drifted from minor league’s Sacramento Solons to the Ft. Worth Panthers, and finally the Omaha Rourkes where, in 1926, he pitched his last game. Unable to find another baseball franchise willing to gamble on him, Yellowhorse returned to Pawnee where, because of alcoholism and rowdy behavior, his tribal brothers spurned him. From 1927 to 1945 Yellowhorse, a pariah within his tribe, earned barely enough income to sustain himself. Then, in 1945, abruptly and without intervention, Yellowhorse gave up drinking. Now sober, Yellow Horse found steady employment, first with the Class-D Ponca City Dodgers as a groundskeeper and then with the Oklahoma State Highway Department.

By the time Yellowhorse died in 1964 at age 66, he had turned his life around and had earned all Pawnees’ respect. Still, Yellowhorse’s Northern Indian Cemetery gravesite is evidence of Indians’ undeserved second-class citizen status. Gravediggers placed Yellowhorse’s headstone in a remote corner in the Indian part of the cemetery which is separated from the white section by a long row of cedar trees.

Footnote: American Indian scholars have learned through their interactions with tribal elders that Indians do not want to be called Native Americans and most certainly not referred to by the politically correct, all-inclusive term “indigenous people.” To preserve their rich but vanishing history, Indians want to be called Indians.

Joe Guzzardi is a Society for American Baseball Research member. Contact him at guzzjoe@yahoo.com

One of the benefits of reading these baseball columns is discovering the neat names of those early teams. Love it! This piece is extra special because of the footnote. Thanks, Mr. Guzzardi!