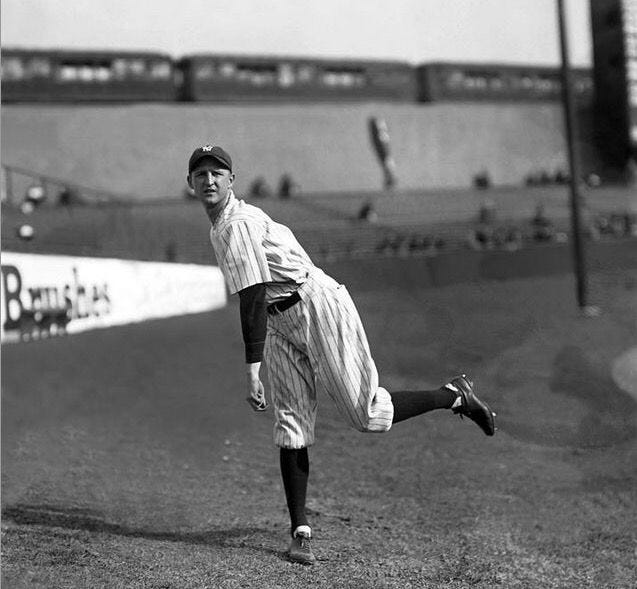

Lefty Grove

On Independence Day 100 years ago—July 4, 1925—50,000 baseball bugs flocked to Yankee Stadium to watch the traditional holiday doubleheader between two teams that had fallen from their American League pinnacles. “Bugs” and “cranks” were common parlance for “fans” in the early 1900s.

The Philadelphia Athletics, led by manager/owner Connie Mack—"Mr. Mack" to the baseball world—were between two dynasties. Mack had led his A's to pennants from 1910-1914, and with his $100,000 Infield and pitchers Eddie Plank, Albert "Chief" Bender, and Rube Waddell, won three World Series during that period. But when the nascent Federal League raided MLB teams, Mack chose not to engage in bidding wars for his players. Instead, he sold or traded his superstars and rebuilt a second dynasty that included Hall of Famers Al Simmons, Mickey Cochrane, one of baseball's best hitting catchers, and Jimmy Foxx, who hit 30 or more home runs in 12 consecutive seasons and drove in 100 or more runs in 13 straight campaigns.

The Yankees had also plunged from American League royalty. In 1925, the Yankees would finish in seventh place with a 69-85 record, 30 games behind the pennant-winning Washington Senators. The team's biggest concern in 1925 was Babe Ruth's illness, also referred to as the "Bellyache Heard Around the World." Ruth had persistent high fevers during spring training, and after an early-season game, he fainted at an Asheville, North Carolina train station. Upon arrival in New York, the Yankees rushed Ruth to St. Vincent's Hospital, where surgeons operated. Some reports claimed it was influenza, but this wasn't the consensus opinion. Whispers circulated that he might never play again and that "the true nature of his illness was being kept secret"—an inference that the culprit was, at best, excessive hot dog consumption or too much bootleg whiskey, or at worst, venereal disease. Concerns about Ruth's fate spread worldwide. Sportswriter W.O. McGeehan penned the lasting story that Ruth's ailment resulted from eating a dozen hot dogs, and a legend was born. The Dundee (Scotland) Daily Telegraph headline read: "BASEBALL FANS GET SHOCK: IDOL OF THE CROWDS REPORTED DEAD!"

A few days after Ruth's release from St. Vincent's, on June 1, Ruth made his 1925 debut. Since Ruth had only been back in the lineup a month, Independence Day fans harbored modest expectations from the great Bambino. In 1925, Ruth suffered through his worst season. For most players, batting .290 with 25 home runs in half a season would be outstanding, but not for the Sultan of Swat.

Although fan expectations may have been diffident, in Game One they witnessed one of the greatest all-time pitching performances between two Hall of Fame left-handers: the Yankees' Herb Pennock and the A's Robert Moses "Lefty" Grove. The hurlers had dramatically different personalities and pitching styles. Pennock was a laid-back, humble Pennsylvania Quaker who placed soft curves on the corners; Grove was a short-tempered flame-thrower. Baseball historians rate Grove as one of the three best left-handed pitchers ever, along with Warren Spahn and Sandy Koufax. Grove's nine ERA titles, seven strikeout crowns, and his .680 winning percentage, 300-141, represent the highest among 300-game winners and is the sixth-best overall in the modern era.

Herb Pennock

When Pennock took the mound, cranks settled back to watch the crafty lefty set down batters one-two-three. A big zero went up on the scoreboard for the A's. More zeros followed through 15 innings. Pennock's challenge was Grove, who matched the crafty Kennett Square hurler goose egg for goose egg until the bottom of the 15th, when Yankees catcher Steve O'Neill knocked in the winning run with a sacrifice fly.

Pennock faced 47 batters—two over the minimum—surrendered four hits, struck out five, and didn't walk a batter. After the game, Grove said, "I was breaking my back trying to knock bats out of their hands, and Pennock was just lobbing the ball up there." Once on the A's roster, Pennock was the player the savvy Mack always regretted releasing. In World Series play, Pennock amassed a 5-0 career win-loss record with three saves, becoming the second pitcher to win five World Series games, after another A's ace, Jack Coombs. Pennock was part of seven World Series championship teams ---1913, 1915, 1916, 1923, 1927, 1928, and 1932---, though he played on four other World Series winning teams as an active member.

Although not as spectacular as Pennock in World Series play, Grove posted a 4-2 record with a 1.75 ERA. After Grove retired from the Boston Red Sox in 1941, he mellowed, coached youth baseball, and managed his bowling alleys. He passed away at age 75. Pennock, on the other hand, remained baseball-active in his post-playing career. He coached in the Red Sox farm system, then moved up to become the Red Sox pitching and first-base coach. Pennock later became the Philadelphia Phillies' general manager. In 1948, in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel lobby, Pennock, age 53, collapsed and died from a cerebral hemorrhage.

Pennock and Grove were among baseball's best, but their accomplishments are, sadly, fading from fans' memories.

Joe Guzzardi is a Society for American Baseball Research historian. Contact him at guzzjoe@yahoo.com